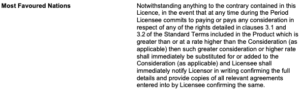

I see MFN (“Most Favoured Nation”) clauses all the time in my day-to-day work in IP rights licensing, and specifically in licensing music for sync. The screenshot above is a classic example, from a licensing agreement I’m working on at the moment.

What is an “MFN clause”?

At its simplest, an MFN clause is a promise that if one party gets a better deal than another, that other party will automatically benefit from the same beneficial terms.

In the areas I work in, this can be very useful. For example you may be a smaller music publisher licensing your share of a song for a sync. It’s reassuring to know you won’t be disadvantaged just because another, larger rights-holder with more bargaining power can negotiate better terms for themselves for their share of the same song, effectively leaving you behind.

In that sense, MFNs can help create fairness and reduce the feeling that smaller players are treated badly. But there’s also something uncomfortable about it. It feels like a rigid, precedent-based mechanism that sits uneasily with the ideal of a flexible, “free market” where every deal is supposed to stand on its own merits. Isn’t there something a bit “anti-competitive” about all this?

I’m not a competition lawyer and don’t claim to be, but we all need to stay mindful of the wide reach of competition law, and the real scope for inadvertently falling foul of it.

I’ve therefore had a look to see what’s going on in the wider world on this topic. Here’s what I found – full references and links to further reading are at the end.

Do you see MFNs in your work? What are your thoughts on how they work now? What might be in store in the future?

What MFNs Mean in Practice

Outside music, MFNs are common in sectors like e-commerce, travel, and digital platforms. For example:

Some countries have reacted strongly:

Where MFNs Bump into Competition Law

So why the scrutiny? Because “Antitrust” (US) or “Competition” (Europe) law is about protecting markets from practices that harm competition and, ultimately, consumers. Authorities look for things like price-fixing, market manipulation, and abuse of dominance.

MFNs can raise red flags because they:

That’s why regulators are increasingly wary, particularly in digital and platform-heavy markets.

Why They’re Not Automatically Unlawful

At the same time, MFNs are not automatically anti-competitive. They are judged case by case.

This means MFNs exist in a grey area. Sometimes helpful, sometimes harmful, but not illegal “per se”.

Where This Could Go Next

With markets shifting towards platforms and algorithms, regulators are watching MFNs more closely:

My Takeaway

MFN clauses are not unlawful in themselves, but their use does seem to be increasingly tested against the question of whether they protect fairness or stifle competition. That’s a tension worth being aware of.

In IP rights licensing, I’ve seen MFNs used in positive, protective ways, particularly where there are clear power imbalances. But the rigidity of the approach feels at odds with the supposed freedom of market economics. Further, the regulatory tide is turning against the broad use of MFNs in platform contexts.

I’ve looked into this area in the context of MFNs because they crop up so often in my work. The sector I operate in is already heavily shaped by market consolidation and shifting consumer behaviour. It has also been largely platform-centred for years. If regulators are scrutinising MFNs in other industries (especially those which are similarly platform-centred), it would be wise for all of us in rights licensing to learn from their experience.

References and further reading:

Apple e-Books:

United States v. Apple, Inc., 952 F. Supp. 2d 638 (S.D.N.Y. 2013), affirmed 791 F.3d 290 (2d Cir. 2015).

Background: Apple and publishers used MFNs in eBooks contracts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_v.Apple(2012)

https://www.quimbee.com/cases/united-states-v-apple-inc

Amazon parity clauses:

European Commission and US investigations into Amazon’s price parity / MFN practices with third-party sellers.

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_5166

Booking.com rate parity clauses:

German case law, OLG Düsseldorf, 4 June 2019 (Higher Regional Court of Appeals).

https://www.cuatrecasas.com/en/global/art/booking-com-victory-over-hotels-in-germany-preventing-hotels-from-offering-prices-lower-than-those-on-booking-com-is-not-anticom

Booking.com before the CJEU:

Case C-264/23, Booking.com BV & Booking.com (Deutschland) GmbH v. 25hours Hotel Company Berlin GmbH & Others.

https://www.traverssmith.com/knowledge/knowledge-container/price-parity-most-favoured-nation-clauses-come-before-the-court-of-justice

Hotel rate parity clauses (Booking.com and Expedia) – legal developments in France and Italy.

https://www.osborneclarke.com/insights/hotel-rate-parity-clauses-legal-developments-in-france-and-italy

Booking.com targeted in new UK class action – Global Competition Review, September 2025:

https://globalcompetitionreview.com/article/booking-targeted-in-new-uk-class-action